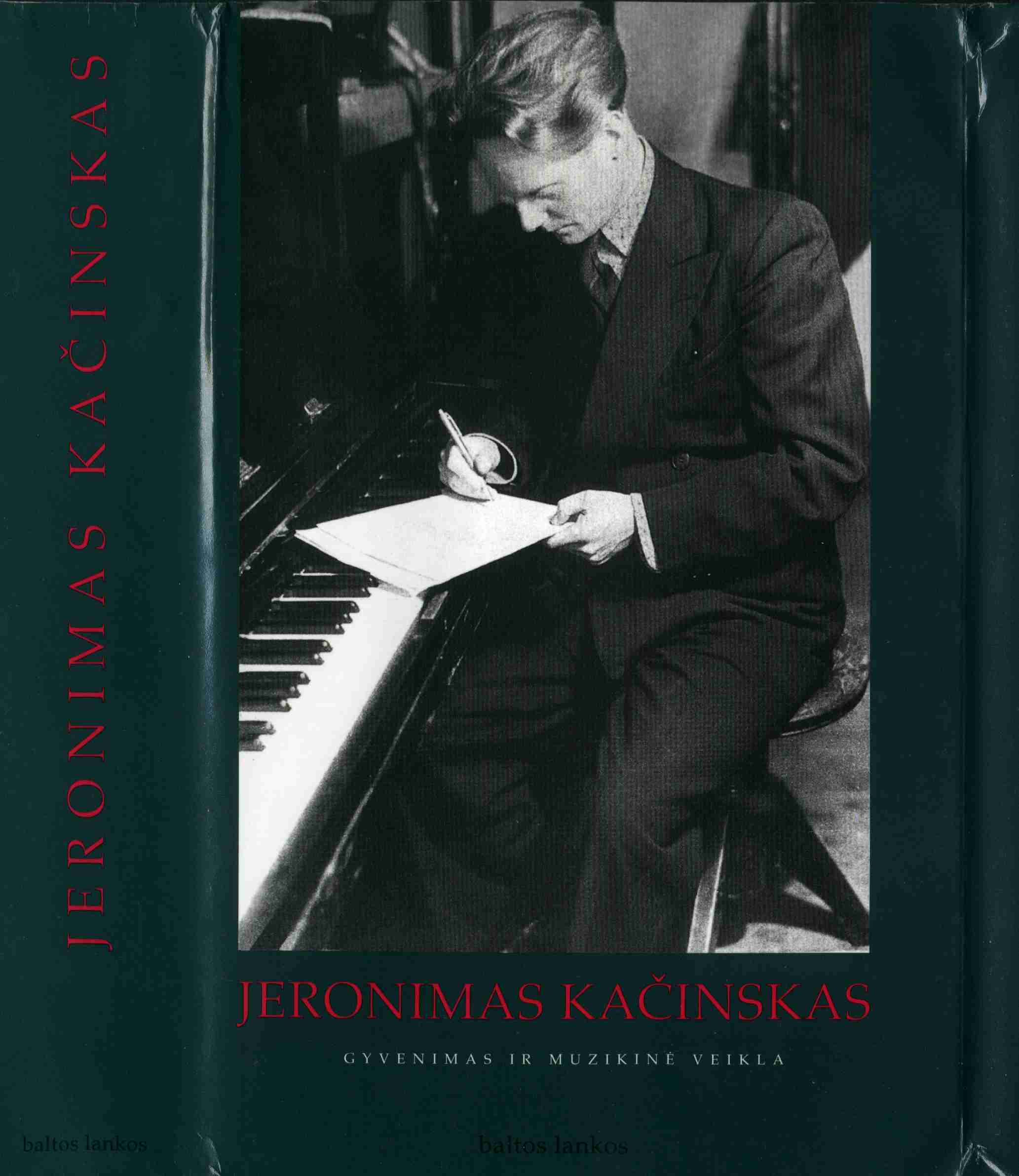

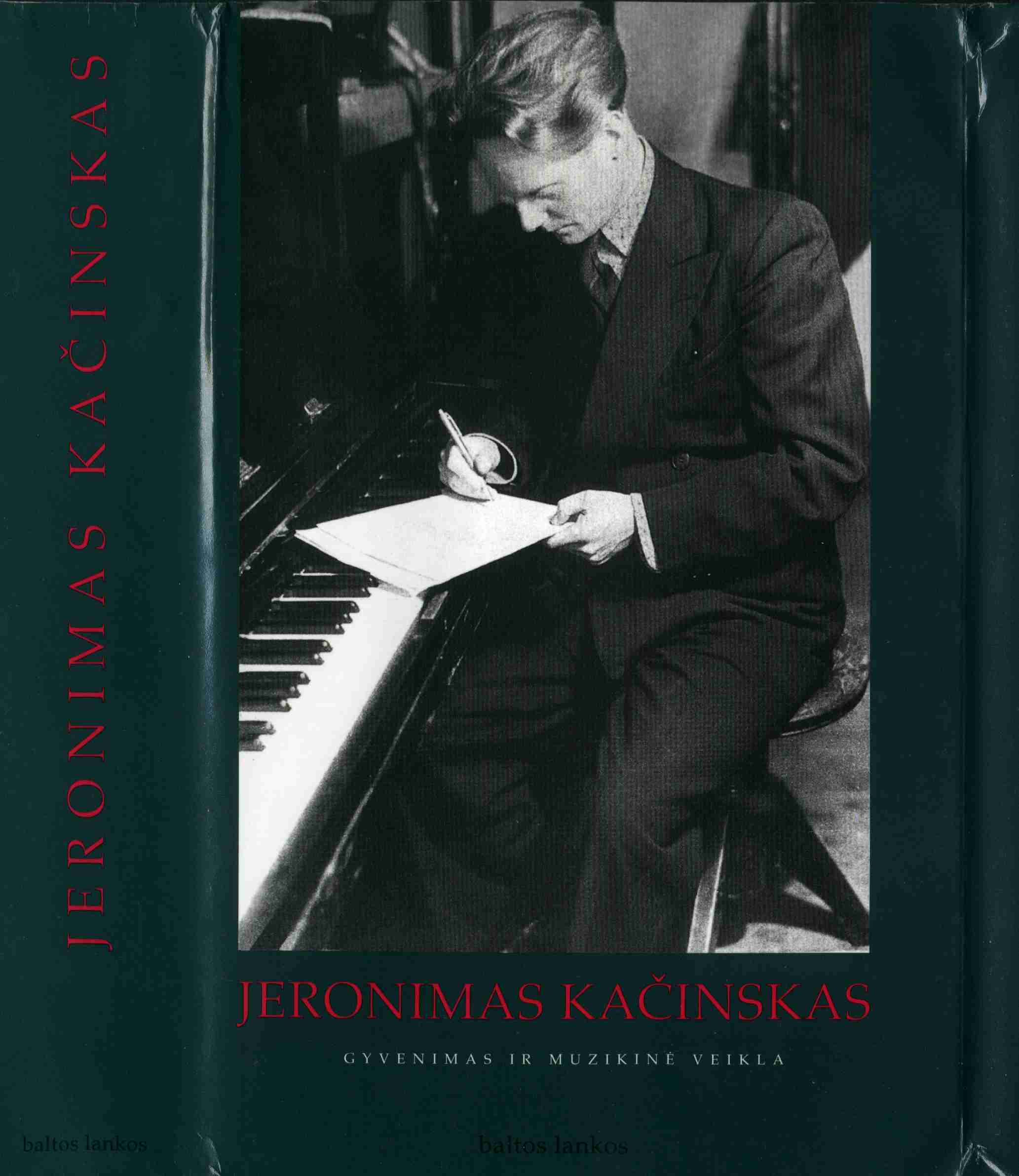

Jeronimas Kacinskas is an outstanding 20th century Lithuanian composer and conductor. He lived and worked in Lithuania till 1944, but after his Motherland had been occupied by the Soviet Union, he moved to the West. There he continued his musical activities and is continuing his work in Boston to this day. In Lithuania, Kacinskas was known as one of the most original artists who defied conventional ways of thinking and for whom a compose was first of all to express individual, rather than a collective consciousness; he prioritized imagination and intuition, but not academical clichés, and thus accelerated the subjectivisation processes of creative activities. Some compositions of Kacinskas became an inseparable part of Lithuanian culture, and the composer is considered to be a classic of the Lithuanian modernism for the first half of the 20th century. Kacinskas has always been supporting the idea of an open society and personality. In Lithuania, he attempted to decentralize musical life and integrate it into the context of Western European art development. He was all for creative and flexible relations between an individual and folk traditions; he tried to find a proper place for the Lithuanian music on the concert stage, and did his best in accumulating progressive innovations in different fields of music. While in exile, he wanted music to help his compatriots to survive the loss of the Motherland and to represent Lithuania in a foreign land on the highest cultural level. Even in the Soviet times, when the names of emigrant artists were removed from the national annals of culture, in the historical memory of the Lithuanian musical society passed from generation to generation, Kacinskas remained an independent and proud creator who influenced indirectly the formation of the Lithuanian composers' school for many decades to come. Kacinskas had better luck than many of his compatriots in exile: he lived to see the rebirth of Lithuania, he came to his free Motherland and enjoyed listening to the performance of his compositions.

This book is dedicated to the 90th birthday anniversary of Kacinskas, and it is an attempt to disclose a wider panorama of musical activities of the composer and conductor, as well as his noble personality. The book consist of two parts: 1) a review, which reveals the most significant features of Kacinskas' creative activities; 2) articles and letters by Kacinskas, as well as his memoirs presented exclusively for this book. Appendices contain a bibliography and discography, the most important dates of life and work of the composer, and the list of his compositions (published also in English). In the process of compiling this book, the author has used materials from archives and libraries in Lithuania and abroad. The author is especially grateful to Kacinskas and his wife for a long-time friendship, to Dr. Jonas Rackauskas, Head of the Chicago Lithuanian Research an Studies Center, to Dr. Warrick L. Carter, Provost of Berklee College of Music, John Bavicchi, Professor Emeritus of the same college, and to many others for moral and financial support.

Kacinskas was born in Vidukle in 1907. He started learning music at the age of 6 with his father, a church organist. With the beginning of World War I, his studies were interrupted, as Kacinskas together with his family were evacuated to Russia. He resumed his studies in 1918, after coming back to a restored independent Lithuania. Kacinskas would play all the compositions he could find in his father's library. At that time he also started composing. In 1923, he finished the Vieksniai secondary school, and upon the advice of his father entered the Klaipeda Music School (Conservatoire).

In Klaipeda, Kacinskas studied the piano, and from 1925, the viola. He played in the school symphony orchestra, in different chamber ensembles, and led the male choir of his school. He also attended additional classes of composition under S. Simkus, and after S. Simkus had left, under J. Zilevicius. At that time, he was distinguished for his diligence, erudition, remarkable progress and original musical thinking. Composed his first works under the influence of impressionism and expressionism. In 1929, Kacinskas decided to continue his studies in the Prague Conservatoire due to the unstable situation the Klaipeda Music School and encouraged by the Czech teachers, who worked in that school and who won authority with the students.

The professors of the Prague Conservatoire were impressed by Variations for the Piano by the young Lithuanian author, but his knowledge of other subjects was not so impressive. He was enrolled in the final year of the composition class on one condition: he had to master the syllabi of all the theory subjects in the course of one year. In the spring of 1930 he graduated from J. Kricka composition class with his First String Quartet, and in a year he got his B. A. in the conducting class.

During Kacinskas' studies in Prague, the greatest influence on his world outlook and the formation of his musical language was made be Professor Alois Hába, a creator and propagator of microtonal and athematical music. The young composer was fascinated by the gentle consonances appearing due to the split semitone, new shades of the mode, and especially the possibility given by athematism: to express oneself freely and not to be bound by traditional canons. A. Hába was discerning thematism, i.e. repetition, in the population of fauna and flora, in some forms of mankind's existence, while athematism was related to manifestations of individualism, to the spiritual qualities of human beings and to the superior cosmic forces able to develop primitive biological structures into the extremely complicated human constitution. Kacinskas was critical about quite a number of his contemporaries' compositions because of plentiful transference and dubbing, and when studying in the studio of A. Hába, he expected to implement the professor's ideas and enrich music by these new means of expression. J. Kacinskas became one of A. Hába's most favorite students. It did not take him long to grasp the laws of quartertone music, he mastered the athematic style, and in 1931, when graduating from the studio, the composed the Second String Quarter in quarter-tone system. A. Hába tried to persuade Kacinskas into staying in Prague, but he wanted to go to Lithuania as soon as possible.

In the fall of 1931, Kacinskas settled down in Kaunas, the provisional capital of Lithuania (Vilnius at that time was occupied by Poland). He wanted to get involved in the musical life, but failed to get a proper job. He had to work as an accompanist, yet he did not lose hope to rise to the conductor's platform ant to open a class of quartertone music. Alas, only a few times did he get a chance to conduct the Symphony Orchestra of the State Opera House. During this time, the course on quartertone music, which he had started to teach at the Kaunas Music School was stopped by the principal's order. The conservative musical society in Kaunas, was quite suspicious of the radical moods of the composer, yet even in this unfavorable environment, he managed to form the Association of Progressive Musicians of Lithuania. At the end of 1931, together with some like-minded people, he started publishing a journal Muzikos barai (Fields of Music), and in this way he hoped to propagate modern music, to speak about the urgent issues of musical life. Kacinskas was supported by his friends in Prague; A. Hába, K. Ancer1, M. Ocadlik, K. Reiner would send articles for his journal. Kacinskas worried a lot about the onesided estimation of professional music on the criteria of nationalism, about neglected lessons of music at comprehensive secondary schools and outdated methods of teaching. He worried about the repertoire of the State Opera House and the principles of selecting staff members, the decline of choral culture and shortage of choral literature. Kacinskas tried to compensate for the shortage, by publishing songs of his own and those of other young composers in the supplement of the journal Muzikos barai.

In 1932, the composer produced one of the most significant of his early works: Nonet for the string and wind instruments. He took the score to Prague, presented it to the Czech Nonet and invited the famous group to visit Lithuania. In 1932, during the tour of Baltic States, the Czech Nonet came to Lithuania. Its programme included the new composition of Kacinskas, and it received some rather contradictory estimations. Most of the audience was used to the music of Classicism and Romanticism, and they found it difficult to grasp the atonal and athematical way of composing music. The reaction of the audience was cool or even derisive. Still, one has to admit that the performance of the Nonet by Kacinskas in Lithuania was a significant event not only for the composer, but also for the musical life of the whole country, which expanded the space of his artistic ideas.

At that time, Kacinskas had already moved to Klaipeda, as he saw no future perspectives in Kaunas. Kacinskas was cherishing a dream to enrich the musical culture of Lithuania with the quartertone music. He was planning 1) to get special instruments for performers and to establish different ensembles for this kind of music; 2) to teach quartertone music at the music school and to train composers and performers in this field. Kacinskas himself had bought a quartertone harmonium and was helping others to acquire instruments of this type, but he failed. The instruments were very expensive, and not everybody could afford them, while a quartertone class established in Klaipeda did not last long: students with a poor theoretical background soon lost interest in the new subject. Kacinskas wrote about it in his letters to A. Hába.

In Klaipeda, Kacinskas led the obligatory piano classes, and a chamber ensemble class, as well as different choirs in the town. But his greatest efforts were directed to the restoration of a symphony orchestra and establishment of an Opera House. In 1933, together with the most capable teachers and students of the music school, as well as instrumentalists from the town, he started organizing concerts of symphony music. In December 1934, the premiere of "La Traviata" by G. Verdi took place. Yet it was difficult to hold concerts, as the performers were not receiving any material support. In 1935, F. Chaliapin visited Klaipeda and was impressed by their enthusiasm. In the spring of 1935, another opera, "Faustus" by Ch. Gounod, conducted by Kacinskas, was performed, but that was the last premiere. Soon the Opera House was liquidated, and in 1936, the Symphony Orchestra also finished its activities.

In the autumn of 1936, Kacinskas tried once again to get the job of a conductor at the Kaunas State Opera House, but after six months of futile attempts he came back to Klaipéda. Kacinskas played the viola in the school's string quartet, acted as an accompanist for soloists, played an active part in the choral movement, and when invited, he never refused to conduct a symphony concert for the Kaunas State Radio. Although not much time was left for creative work, the composer still did not give up his idea to enter the international music arena.

In 1936, Kacinskas applied to the International Society for Contemporary Music, asking to accept Lithuania as its member. The applying country had to distinguish itself in the field of modern music and to get a recommendation from a member country. Kacinskas got the recommendation from Czechoslovakia, and his request was complied with. In 1937, a festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music took place in Paris, and Lithuania was the first Baltic republic to participate as a member with equal rights. It was represented by the composers Kacinskas and V. Bacevicius, later, they were joined by V. Jakubenas. Programmes for the concerts consisted of compositions selected by jury. In 1938, the jury chose Nonet by Kacinskas, and performed by the Czech musicians, it became one of the most interesting items at the London festival. The author was congratulated by composers of different countries, Bela Bartok among them. In 1939, the Warsaw Festival was the last for Kacinskas, as Lithuania, occupied in 1940, lost its membership and renewed it only in 1991, when it became an independent state once again.

The Lithuanian government did not support musical institutions, and the cultural life in Klaipeda was inactive. At the same time the local German nationalists were becoming more and more active. That's why in the fall of 1938 Kacinskas accepted the job of a conductor of the Symphony Orchestra for the State Radio and left for Kaunas. At that time concerts were not recorded, and the music went directly on the air. Kacinskas would include works by composers of different countries and epochs in the repertoire of his orchestra. Kacinskas performed almost all of the symphony works by Lithuanian composers. From England he received an official message of thanks for popularizing English music in Lithuania.

At the beginning of 1940, when Vilnius was returned to Lithuania, the Radio orchestra moved to the old capital. The work rhythm remained the same: two concerts a week directly on the air and a public performance about once a month. With the Soviet occupation, the orchestra received a hard blow. The communist authorities introduced censorship on the programmes, forced compositions of Soviet authors on the orchestra. On the other hand, the Hitlerites were also pointing out which compositions were to be performed and which not, they dismissed the performers of the Jewish nationality from the orchestra, and in 1941, transferred the orchestra to the disposal of the Vilnius Philharmonic Society. Kacinskas was happy to have escaped from the immediate supervision of the Nazi. Kacinskas regularly organized public concerts of symphony music, he was one of the first in Lithuania who started teaching orchestra conducting at the Vilnius Music School. In 1942, when an Opera House opened in Vilnius, he became a conductor in it. Under his supervision "La Traviata" by G. Verdi, "Madame Butterfly" by G. Puccini, "The Barber of Seville" were staged. In the opinion of some musical critics, Kacinskas was one of the most productive and best conductors in Lithuania. As the leader of the Radio and Philharmonic orchestras, he arranged about 450 public, closed and radio concerts and conducted in about 250 performances in the Vilnius Opera House.

With the front approaching Vilnius, Kacinskas found out that communists had included his name in the list of people condemned for either death or exile, and therefore decided to leave Lithuania. His journey to the West started in the fall of 1944. He had to hide starve and suffer illnesses, as well as to get used to the idea that all his manuscripts perished. Kacinskas stopped for a time in the Czech town Lednica (Eisgrub) occupied by the German Nazi. He made his living by doing hard manual work. The composer had hoped to find a job in Prague with A. Hába's help, but he found out that the Soviets were already there. It was due to a happy coincidence that Kacinskas managed to escape, and in the fall of 1945 together with his wife he settled down in Hochfeld, a suburb of Augsburg, in the zone controlled by the Americans.

In Augsburg, a few thousands of Lithuanian refugees found shelter. To preserve their traditions and culture, they sought to lead an active cultural life. Kacinskas got involved in it immediately. He was the leader of a mixed choir, acted as an accompanist for singers, arranged concerts and composed music. At that time he composed his best songs for the choir. He managed to get in touch with the Augsburg Symphony Orchestra, and together with the Latvian and Estonian musicians they gave a few concerts of symphony music. Work with an orchestra stimulated the composer to go back to writing symphony music, while playing the organ in the church brought him liturgical themes.

In 1947, Kacinskas, like most of other refugees, started worrying about a safer shelter, as it seemed dangerous for him to stay in Europe. Therefore he applied to his old acquaintances -V. Bacevicius and J. Zilevicius, residing in the USA, and they helped him to get an entry visa. In the spring of 1949, Kacinskas accepted the invitation of the priest of St. Peter's Lithuanian parish in Boston, and started work as an organist there.

Lithuanians had been living in Boston since the end of the 19th century. To preserve their national identity, they had been establishing their organizations, associations and schools, yet the traditions of their cultural life were very different from those in Lithuania. It was not so easy for Kacinskas to work with the church choir. The choir singers were content with the usual liturgical repertoire, while the new conductor tried not only to include some new compositions of religious music, but also to prepare programmes of secular music. Yet due to Kacinskas' persistence the choir of St. Peter's church became a cultural center for Lithuanians. He was regularly arranging concerts in Boston and its environs, participated in music festivals organized by other ethnic communities. Despite that, the job of the organist restricted the composer. He lived in a very closed and, from the artistic point of view, limited community of his compatriots. That's why he tried to integrate himself into American musical life. It was not an easy task to do. The Americans did not know much about immigrant Lithuanian artists, and even if they knew, they could hardly accept them because of the huge competition in all fields of cultural activities.

In 1951, Kacinskas produced one of his most significant works, the Mass dedicated to the anniversary of the Christening of King Mindaugas. In it he masterfully combined consonance of the Gregorian chant and of the Medieval organum with bifunctional complexes popular in the 20th century, with the quartal chords, extended tonality and his favourite athematism. The Lithuanians found the Mass too innovative.

The Lithuanians, even they failed to understand the atonal and athematic music by Kacinskas and were not always able to perform it, valued him as a conductor. In 1952 the Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians arranged a concert of symphony music at Carnegie Hall with a joint NBC Radio and New York Philharmonic orchestra, and in 1953, during the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the Christening of King Mindaugas, Kacinskas performed with the Washington National Symphony Orchestra. The Americans were impressed with the professional performance of Kacinskas, but after finding out he was just a church organist, they refrained from any serious offers. Thus Kacinskas stayed in St. Peter's parish, devoting most of his time to the church choir and composing musical works.

Kacinskas started looking for a job somewhere else. About 1956, he made the acquaintance of John Bavicchi, a graduate of the New England Conservatoire and Harvard University. With the encouragement from J. Bavicchi, Kacinskas wrote a cycle for the piano "Atspindiai" (Reflections) and Four Miniatures for the flute, clarinet and violoncello. The compositions were a success with both the American and Lithuanian performers and were performed in different concert halls. In 1958, the composer accepted a job of an organist in the Slovakian parish in Whiting, Indiana, and left Boston, but not for long. In half a year he was back, as the new place did not offer good working conditions.

Kacinskas was one of the enthusiasts who tried to show that the Lithuanians are capable not only of dancing folk dances and singing folk songs, but also of cherishing their elite culture. That's why he tried to persuade his compatriots in Boston into preparing a programme of Lithuanian symphony music. He finally managed to do it in 1958, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The concert was a success, the Americans learned more about Kacinskas, and more possibilities of cooperation opened for him. In 1959, he was invited to conduct the Brockton Symphony Orchestra, in 1960 - the Cambridge Civic Symphony Orchestra, and in the fall of 1960, with the recommendation of J. Bavicchi and having passed the competition, he became a permanent conductor of the Melrose Symphony Orchestra, one of the oldest orchestras in the environs of Boston.

The fruitful cooperation between Kacinskas and J. Bavicchi continued. They had been arranging joint concerts of Lithuanian and American music and had been active members of the Association "The Institute for Progress in Music". With the widening of his audience, the composer had a stimulus for creative work. In the 60s and 70s he wrote a few large symphonic works. However, in his opinion, he was more successful in chamber genres, so he moved in that direction.

Americans liked the Lithuanian musician and started inviting him to many places. They asked Kacinskas to take the lead of the choir "Polymnia" in Wakefield in 1965, and the composer accepted. It was good for the choir singers of St. Peter's parish as well, as on many occasions the conductor would invite additional singers and instrumentalists to the concerts. The Americans would gladly perform not only the classical repertoire, bet also the works by Lithuanian composers. With Kacinskas conducting different orchestras in the USA, works by V. Bacevicius, K. V. Banaitis, M. K. Ciurlionis, J. Gaidelis, J. Gruodis, V. Jakubenas, S. Simkus and Kacinskas himself were performed. The compositions by Kacinskas were performed on the initiative of the Americans. The Belmont Community Choir under the leadership of J. Bavicchi had been performing songs and the Mass by Kacinskas, while the instrumentalists on the occasion of the composer's 60th birthday arranged a concert of his works.

In 1967, Kacinskas started teaching conducting and composition at the Berklee College of Music. That meant he had to give up the "Polymnia" choir and the Melrose Symphony Orchestra, but he continued working as an organist for the church. A new job meant new contacts. The composer was approached by performers commissioning compositions, which were immediately performed in the concerts by the College's faculty. Kacinskas was self-critical about his works, but never criticized other authors, trying to find something good even in the most unsuccessful composition.

Kacinskas had spent nineteen years in the Berklee College of Music with its benevolent and creative atmosphere, and had produced a number of compositions there. He never ignored requests from the Lithuanians: he would compose cantatas, motets, hymns for their religious and national festivals. One of his largest compositions in the 80s was an one-act opera "Black Ship", staged by the Chicago Lithuanian Opera. By this work the composer proved that atonal music can be melodious, sound in a natural way and be understood by any listeners. Creative activities by Kacinskas were often commented upon by the Lithuanian periodicals sometimes even by significant American newspapers. The opinions of the American musical critics were contradictory.

In 90s, new tendencies in Kacinskas works were revealed, elements of Lithuanian intonations appeared; earlier, the composer had consciously avoided them. As Kacinskas himself explained, he was greatly influenced by composers residing in Lithuania. As a result, he stopped avoiding reprises or contacts with tonality. However, Kacinskas felt that the direct Lithuanian manner was limiting him, this he stayed with his old principles of composing, and just treated them in a more free way. But even in his atonal and athematic music one could feel the Lithuanian spirit- visuality of pastel colours, the sense of transparent sadness, lyrical melancholy or restrained joy ant the lyrical-mystical world outlook.

In Soviet Lithuania, the name of Kacinskas has not been mentioned frequently. Sometimes one or another song by him would be performed but on the whole, his music was little known, and official institutions recommended not to take an interest in it. Kacinskas was considered a representative of the formalism of Western Europe which was contradictory to the realistic national school of composers. But the Lithuanian people hadn't forgotten either his name or his deeds. At the end of the 90s, with the warmingup of the political climate in Lithuania, concerts of his compositions were held. The Lithuanian Composers' Union elected him Honorary Member and invited him to visit his Motherland. Changes in his country were glad tidings for Kacinskas and inspired his new works. This was an inspiring period for him. The composer visited Lithuania in 1991. The musical community took a great interest in the visit. In the major cities of the country his concerts took place, and after them many people wanted to talk to the famous musician of the independent Lithuania who had been out of reach for a long time. The people of Klaipeda elected him Honorary Citizen of their city, and the residents of Vilnius nominated him for the 1991 National Prize. He received the Prize in 1992, during his second visit to Lithuania. Renewed ties with Lithuania accelerated the retirement of Kacinskas: after it, the composer could devote all his efforts to creative work and to writing his memoirs, as well as to St. Peter's parish choir.

When the composer himself reviews his works, he admits, that as a supporter of a free creative process and a rebel against traditions in music, he had dived into dense complexities of music, and into an unrestricted texture, complex harmonies and complex changes of melodies. His admiration for athematism has made the development of the continuity of a musical idea hardly tangible. He cannot strictly divide his compositions into periods: stylistic elements of different trends criss-cross in different ways and make periods difficult to define. Kacinskas thinks the first period of his creative activities, with radical expressionism and maximalist standpoints, lasted from 1929 till 1952. The period of modem moderate style with almost imperceptible features of romanticism followed. The American technicalities has influenced him for a short time and left traces in only a few compositions. The period of 1970-1980 was for Kacinskas the time of search, after which he started using intonations of Lithuanian folk songs without giving up either athematism or atonality. Today the composer's attitude towards athematism has changed. He no longer thinks that only athematic music can express the artistic potential of an individual in the best possible way, and offer s many examples where masterful use of repeated tunes can perfectly disclose changing spiritual states of man and his environment; but at the same time he admits the technique is unacceptable for him. For Kacinskas a composition is a kind of improvisation , but a strictly fixed one. Before starting work, he thinks for a long time. The idea s are born slowly, sometimes spontaneously, yet at the start there is no knowing where they will take him. The composer does not base himself on a strict sound organization set in advance or an detailed structuralism. Atonality also appears not from a specific series, but rather as if a result of chromatized sounds. In all the parameters of music, there is a distinct asymmetry which brings out the significance of the horizontal line and creates the impression of an endless form. Kacinskas considers his youthful admiration for quarter-tones to be a natural need to participate in the process of the renovation of music language; as it turned out, later, because of a rapid development of the electronic industry and of the production of synthesizers, the idea lost its significance. He never regrets having emigrated in 1944, as he can not imagine himself an author of cantatas glorifying the Communist party ant its leaders. On the other hand, he admits that living abroad, he had to adapt to performers of different levels and make concessions to them. The composer claims that his vocal, and especially choral, music, with the exception of his opera "Black Ship", is more or less in the nature of a compromise. It is wither too old fashioned nor vanguard, just like his instrumental music. Modem music for Kacinskas has always been a step towards the progress of culture. Even now he is trying not to lag behind too much, but doesn't think he has to rush after rapid changes taking place in music. After all, such moves may be too late for him, being on the threshold of the 90th birthday. He is satisfied with the synthesis of the musical trends in the first half of the 20th century, as it grants him the most of creative freedom. Only the strict dodecaphonic method seems too rational, and therefore unacceptable for Kacinskas. For him art is a fusion of emotions and intellect.

In exile, having lived in despair for a long time and foreseeing no future for his works, Kacinskas stopped registering both his compositions and concerts, which makes it difficult to state exactly how many times he went to a conductor's platform in the USA. He must have conducted symphony orchestras at least 50 times, and choirs probably three or four times more. He estimates having written about 100 compositions, starting with short hymns and finishing with large vocal-instrumental works. All of them are more or less dear to him, but neither is considered perfect by the author.

In Boston Kacinskas misses his Motherland, yet doesn't want to change his residence. He tries to overcome the distance across the Atlantic Ocean by reading Lithuanian periodicals and closely cooperating with the Lithuanian musicians. He is also very much concerned with the activities of the Lithuanians in the USA, making an integral part of the manifold musical culture of that country.

Copyright © Danute Petrauskaite 1997